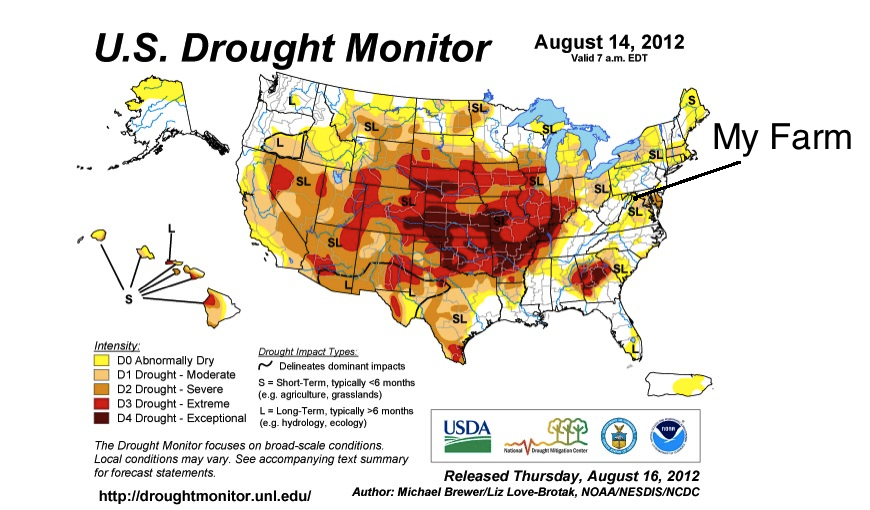

My heart goes out to my fellow farmers who live within the drought stricken region that now stretches almost nationwide. As you can see from the map, my own farm hasn’t been immune to the lack of rainfall (most of Virginia is currently experiencing ‘abnormally dry’ to ‘moderate drought’ conditions), but my region is in vastly better shape than most of the country. Having suffered through an agonizing two year drought in the 1990s, I can truly empathize with my peers. Nothing is quite as demoralizing as waking day after day to a parched, withered landscape, knowing that if only Mother Nature would send some refreshing storm clouds our way, everything might change in a matter of days.

My heart goes out to my fellow farmers who live within the drought stricken region that now stretches almost nationwide. As you can see from the map, my own farm hasn’t been immune to the lack of rainfall (most of Virginia is currently experiencing ‘abnormally dry’ to ‘moderate drought’ conditions), but my region is in vastly better shape than most of the country. Having suffered through an agonizing two year drought in the 1990s, I can truly empathize with my peers. Nothing is quite as demoralizing as waking day after day to a parched, withered landscape, knowing that if only Mother Nature would send some refreshing storm clouds our way, everything might change in a matter of days.

Here is a young field of corn in June. Although at first glance this field looks green and vibrant, take a close look at the ground. What do you see? Lots of exposed dirt, incapable of retaining moisture as a hot season progresses. To successfully plant the corn, farmers spray the earth with herbicide, killing off competing vegetation. As long as it doesn’t get too hot, and rains reliably fall, everything is okay. When drought hits, however, this exposed ground will cook as hard as a brick.

The good news is, droughts always end. Rain will eventually fall, and the crops will turn green again… if not this year, then in the future. Fifteen years ago, I suffered through hopeless months of brittle grass crackling beneath my boots, and small puffs of dust billowing with each step I took. I was forced to feed hay to our cattle nearly all summer long, food normally reserved for the depths of winter. Our farm survived through sheer force of will, and faith that the drought would eventually break. If I can offer one wish to my brother and sister farmers out there, it is this: ‘Hang on.’ It will get better.

Those brutally dry years taught me many valuable lessons as I began my farming career. I not only learned the importance (and unpredictability) of rainfall, but of intentionally managing my fields to soak up and retain as much moisture as possible whenever it does happen to rain. Mechanical irrigation isn’t a sensible solution for a farm like mine; I manage roughly 500 acres of pasture and free-range livestock, and it’s nearly impossible to economically water that much land. If the rain doesn’t fall, my soil must be as prepared as possible to endure the drought conditions while they last. By promoting perennial (year round) grasses and clovers in my pastures, and by carefully managing how my animals graze, I can do a lot to control moisture, temperature and fertility levels on my farm. Growing grass might not seem very exciting, but it sure beats planting a field of corn, only to watch it wither away.

Once the heat and drought settled in, I took some temperature readings. No, this isn’t Arizona… it’s Virginia. This reading, taken along the farm’s driveway, mimics the surface temps of an exposed cornfield, where the soil bakes beneath an unrelenting sun.

As I read the national headlines and watch the news reports, I frequently find myself shaking my head at the reporting. A tremendous amount of common sense is either being ignored or overlooked as to what we can all learn from this devastating event. Much of the focus is being inappropriately placed on food price concerns, as though corn and soybeans—the two major crops suffering beneath the drought—are major staples of human food. Journalists, please note: they are not… at least not directly. Nearly all the corn and soybeans grown in America, around 90%, are destined for confinement livestock feedlots (cattle, pigs and chickens raised on concrete, without any access to grass), and ethanol for gasoline. Although food prices will almost certainly rise (estimates are currently around 3-5%), this will result from increased costs of transportation, and the shrinking profits associated with raising factory farmed animals.

Alternatively, this 89 degree reading was taken just a few feet away, in my pasture. The thermometer is sitting in full sunlight, resting on top of the ground, yet the temperature is a staggering 20 degrees cooler than the exposed driveway. Which do you think will evaporate more quickly, water on a sun baked 109 degree surface, or moisture hiding beneath a shaded, 89 degree pasture?

A major national magazine (which shall go unnamed) recently suggested that “corn on the cob” will suddenly be more expensive at the grocery stores. Not to sound patronizing, but does this writer realize that 99.9% of corn grown in the U.S. isn’t the delicious ‘sweet corn’ enjoyed at summer picnics, but unpalatable ‘field corn’ grown for animal feed and ethanol? Another report insists that because agriculture only accounts for 1.2% of our total GDP, the drought won’t have a major effect one way or another on our economy. Seriously? Only 1.2%? Does this number include the trucking and shipping companies that rely on abundant harvests to fill their box cars and barges (see an article on this topic here), or the billion dollar agricultural machinery companies that need farmers to purchase their products? And what about those grocery stores and restaurants that like to sell food to their customers? Did I forget the ethanol refineries? I could easily go on. Sure, agriculture may technically only account for 1.2% of our economy, but its impact is enormous and wide reaching. This drought will certainly impact us all in some way, either through our jobs, or in the checkout line.

Going back to the news for just a second, I experienced a jaw-dropping “are you serious?” reaction when I read this (article here):

Richard Volpe, an economist with the USDA’s Economic Research Service told CNN “Corn is a major input for retail food,” he said. “Corn is used to make feed for all the animals in our food supply chain. As this drought reduces the harvest of corn, that would drive up the price of feed for animals and then in turn meat products.”

With all due respect, not all animals in our food supply chain are raised on corn. In fact, some animals are raised without a single kernel of grain, and instead live their lives eating natural, perennial pasture. My cattle never so much as sniff an ear of corn, much less ogle a bag of soybeans. By focusing in on these journalistic sound bites and misleading statistics, it’s easy to lose track of the greater picture, and the greater opportunity. As farmers and conscientious, connected consumers, we are faced with the difficult task of tuning out voices that insist there’s only one correct path, and that all other options are unworthy of our consideration. But this drought has revealed how deeply connected we all are to our food system, and how truly vulnerable the system is.

Take another look at that cornfield above, then look at this perennial pasture. Wow, what a difference! This picture was taken in mid July, on a 95 degree day. Notice how thick and dense the grass is, even in the midst of a drought. Robert is using a simple step-in post and reusable wire to subdivide this pasture before our cattle enter the field for their daily graze.

Of course, I can already hear the self-proclaimed ‘realists’ raising their chant: “Organic farming and sustainable agriculture is a pipe dream, you hippy! If we don’t raise millions of acres of corn and soybeans, the world will starve to death. Enjoy your high-priced steaks and fancy heirloom tomatoes; as for me, I’ll be the one not starving, thanks to all this cheap, abundant food.”

For these ‘realists,’ I encourage them to take a look at these statistics from the USDA. In 2012, it’s estimated that farmers will plant over 200 million acres of corn, soybeans and wheat combined. While that’s a tremendous amount of grain, there’s also a flip side to this number: the U.S. also supports over 600 million acres of pasture, range and hay fields in addition to these crop fields. Let me repeat his number for effect: 600 MILLION ACRES OF GRASS. Do you see where I’m going, here? Above and beyond all the corn, soybeans and wheat (which are currently being planted at all-time historic highs), there remains over 3 TIMES as much available pasture for animals to be grazing. America clearly has the ability to raise its cattle without ever feeding them a single handful of grain.

Pastures and hayfields comprise over 600 million acres in the United States, more than triple all types of grain fields combined.

So how do pasture, grain, and livestock fit together with the recent weather? In light of the terrible drought, its more important than ever consider these diverse statistics, and understand what they mean for our mutual well being. To me, the numbers suggest that we don’t need to be funneling the majority of our drought-stricken grain towards animal feed. Our underutilized pastures and grass lands could be carrying much higher numbers of free-range, grass fed cattle and sheep if we only focused our manpower and burgeoning experience to manage these underutilized resources.

Furthermore, as farmers nationwide are now realizing, grasslands are far better suited to endure a drought. Well-tended pastures can capture and retain elusive rainfall better than a field planted with crops. Pastures rarely, if ever, need to be planted, sprayed or chemically fertilized. Of course, pastures will eventually fail without rainfall, but the point is that they endure far longer, and with much less expense, than fields of grain currently experiencing drought conditions. Intensively managed pasture may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, but it is an emerging and compelling component in our sustainable food future.

Despite our individual opinions about food policy and production, we’re all deeply connected to our food supply. As terrible as this drought is for thousands of farming families, it’s an opportunity for us to closely examine sustainable practices and alternative methodologies as we move forward. There will always be a naysayer or two in the crowd; let’s patiently indulge them with a nod of the head, but move steadily forward. As the drought breaks, and rain falls anew, a verdant season awaits us with inspiring possibilities.

I really enjoyed this article. Thank you for sharing so much wisdom and encouragement. Are you familiar with the “Back to Eden” film and philosophy? The film shares about how to help the land to retain moisture, among other natural gardening tips. I’m just learning some of this and my daughters and I plan to incorporate more of these natural principles into our gardening practices in the near future. Thank you for sharing.

I’m sold on sustainable agriculture for a number of reasons, but it was refreshing to see a good *economic* argument for feeding animals grass. Too often people will spout off 10 different reasons to go organic or sustainable and it will be dismissed as “too expensive” or “not practical”. When industrial ag runs out of pesticides and herbicides that will keep their crops alive then we’ll see what’s practical after all.

Thanks! And indeed, economics and finance must remain in the forefront of farmers’ minds, especially young or new farmers. Sustainable and organic practices are fabulous ways for farmers to expand margins while simultaneously producing food with freshness, nutrition and transparency.

Splendid story! Will be much forwarded. Thank you.

Great post!!

I enjoyed your piece very much. I live about 6 or 7 miles from you, just across the Shenandoah. I wondered if you:

1. Employ a Voisin system, or some other, and if another, what?

2. Have sod grass or clump grass?

3. Can you graze into or through the winter on existing pasture in a good year?

And:

4. What is your stocking rate?

5. Do you integrate your sheep with your cattle for grazing, or graze them separately?

Thank you very much. I knew your father, and have met your sister a few times. I would like to visit your farm sometime, and my wife and I were going to contact you about buying a side of beef, or perhaps an entire beef if we can get someone to go in with us.

Hi Michael, thanks for the response. Indeed, based on my understandings of Voisin, our farm follows a similar philosophy to the one he espoused. To summarize, I believe there is a strong correlation between soil/grazing animal/human health (the human being consumer of the grazing animal), that pasture rest and rotation are vital to sustainable pasture management, and that photosynthesis, carbon sequestration and nitrogen fixation via legumes (clover, especially) is vital. Not sure about the sod/clump grass question, but we foster perennial grasses that grow well in our climate (orchard grass, blue grass, timothy and (unfortunately, to a certain degree) fescue) that need no additional reseeding or fertilizer.

We typically try to graze until mid February, though last year’s October snowstorm altered our plans! We intentionally feed hay as a fertilizer supplement and seed invigorating philosophy. To generalize, we try to graze to a point in the winter where forage quality is still high, but without scalping the pastures below a 4 inch residue. This helps us retain root strength and moisture going into the spring… and was very important this past March, with little rain and daily highs in the 90s. Yikes!

Our current stocking rate is roughly 225 head of cattle and 200 head of sheep on 420 acres (we manage an additional 80 acres of pasture in West Virginia with smaller numbers). If the translation is 7 sheep to one cow (I think?), this roughly makes our stocking rate 1 cow per 1.5 acres. This is intentionally conservative; we could probably stock 250 head of cattle and 350 head of sheep, but that would be pushing our comfort levels a bit too much. I farm under the constant knowledge that my pastures are only as strong as the next good rain that comes my way. Oh, and indeed, we keep the cattle with the sheep… great dead-end parasite hosts, and good side-by-side grazers, as the sheep really like to eat forbs.

Okay, hope that answers everything, please come visit us sometime!

Have you considered or tried Brome grass? Thanks.

I’ve fed brome grass hay (hay that I bought), and it’s a wonderful forage. Haven’t ever planted any (we let our grasses volunteer), but have heard great things about it.

I like the idea of a sod grass that covers better as a benefit in dry seasons. The less bare earth, the better.

Great article Forrest! Thanks for not following the proverbial “herd” with your farming methods. It’s refreshing to see a movement of so many small-mid size farmers and home gardeners popping up around the country who are using organic and permaculture methods. People are finally starting to reconnect to their food and the people that grow it. Hopefully, in another generation, the west will actually have a diet worth exporting.

@Donna Geddes: The method shown in Back to Eden is also frequently utilized in permaculture. My wife and I have been using this method combined with hugelkultur in our yard for about three years now. They’re highly effective at creating nutrient rich soil that’s teeming with life and requires no water, fertilizer, or plowing. Highly recommend trying it. Here’s a link to students using a revised version of this at U Mass: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWHSzGDItBA. UMass uses a layer of topsoil between the cardboard and the wood chips; Eden puts the wood chips straight on the cardboard. Either method works great, but adding soil brings more worms and other decomposers in to break down the wood chips faster, so you get dirt faster. Using dirt adds a bit more expense though.

Thank you, Aaron, I agree… this is a far-reaching and fundamental shift in the way we think about our food; a collaboration not only between farmer and consumer, but the farmer and the ecosystem. It’s exciting to be a participant!

As to the Back to Eden methods, I think that anything that puts an emphasis on soil building (fostering microorganisms, beneficial molds and bacterias), carbon sequestration and moisture retention is a great thing. Naturally, the scale of one’s operation will determine what works best. Ruth Stout pioneered a lot of this work as well, as a grass farmer, I’m able to mimic her methods via my cattle trampling fully mature grasses, adding a ‘litter’ layer (essentially a living mulch) to the top soil.

Very well written and sums up alot of what I’ve been preaching to my friends and family! Keep up the good work; I’ll be following you on FB based on this article and look forward to more. Thank you for farming the RIGHT way!!

Chad, thank you for reading… I’ll keep doing my best!

Great article! You & me, we think alike. I’m trying to convince people to take more responsibility for their food and grow where they live. I’ve been quit disturbed to watch the evening news, listening to people boo-hoo about the corn & soy, then take my evening walk and see lawn after lawn of well-manacured, well-watered grass. We’ll be buying very little from the grocery store this winter thanks in part to filling our city lot with as much “edible landscaping” as it will hold & 7 spoiled laying hens. My husband hunts deer, my father pastures sheep and grows alfalfa (which he is planning to expand because of a surge in demand. Grass, yes!), & we are going to purchase a 4-H project hog. Our rule is no food from a box or bag, and if more people adopted this way of eating (and tended a garden the way they tend their lawns) we could eliminate the weaknesses of our food supply (namely transportation). Thanks for your time, I’m going to preorder your book.

Thank you for the thoughtful response, Lyndsey. To quote John Lennon, “there are no problems… only solutions.” We live in a country of abundance on so many fronts, especially agriculturally. It’s inspiring to hear that you’re taking such a diversified approach. And a big THANK YOU for pre-ordering the book… it will be available next April.

Great article. (and love the John Lennon quote.) We’re long-time organic farmers putting a new twist into our operation. We’ve decided to stop relying on conventional field growing and convert to a more conservation minded approach for raising our veggies. We’ve found that regardless of the drought in Missouri this summer, our aquaponics crop is doing so much better and is a LOT less day to day work than our organic field crops. We use less than 10% of the water, too. I think that a national mind-shift in this direction could greatly reduce our dependency on corporate farming and fossil fuels, while at the same time assure crop success and water conservation. There ARE better ways to grow food and be responsible to our home planet. Thanks for your perspective. I hope more people become supportive of organic farming and start protecting our precious natural resources.

Hi Connie,

Thanks for the insights. Can you explain a little more about aquaponics, or link to a good explanation? As a livestock farmer, I’m out of this loop! On a side note, I’ve been wondering how Greg Judy (a well known grass farmer and sustainable ag advocate in Missouri) has been doing this summer.

And I agree… if we all act as responsible stewards in our tiny corners of the worlds, the cumulative effects will add up (as will the positive peer pressure!). This movement towards sustainability is happening, but it takes leadership -like you old timers, ha ha- to give the skeptics something to consider. Keep up the good work, and stay in touch!

I loved this article. I am approached all the time by owners in the Midwest that wish not to sell their beautiful pasture based farms to the conventional corn and soybean establishment. I only wish that our company could purchase and preserve all pastures that are so endangered. We have focused on organic farming — starting in Illinois — and are now hoping to expand to Wisconsin and diversify to pastures and grasses. In the process, we educate our members on the true meaning of sustainable agriculture. Thanks for educating us.

David Miller, Iroquois Valley Farms

Thanks, David. I checked out your site, and what you are doing is very interesting. Do you follow Jim Rogers at all?