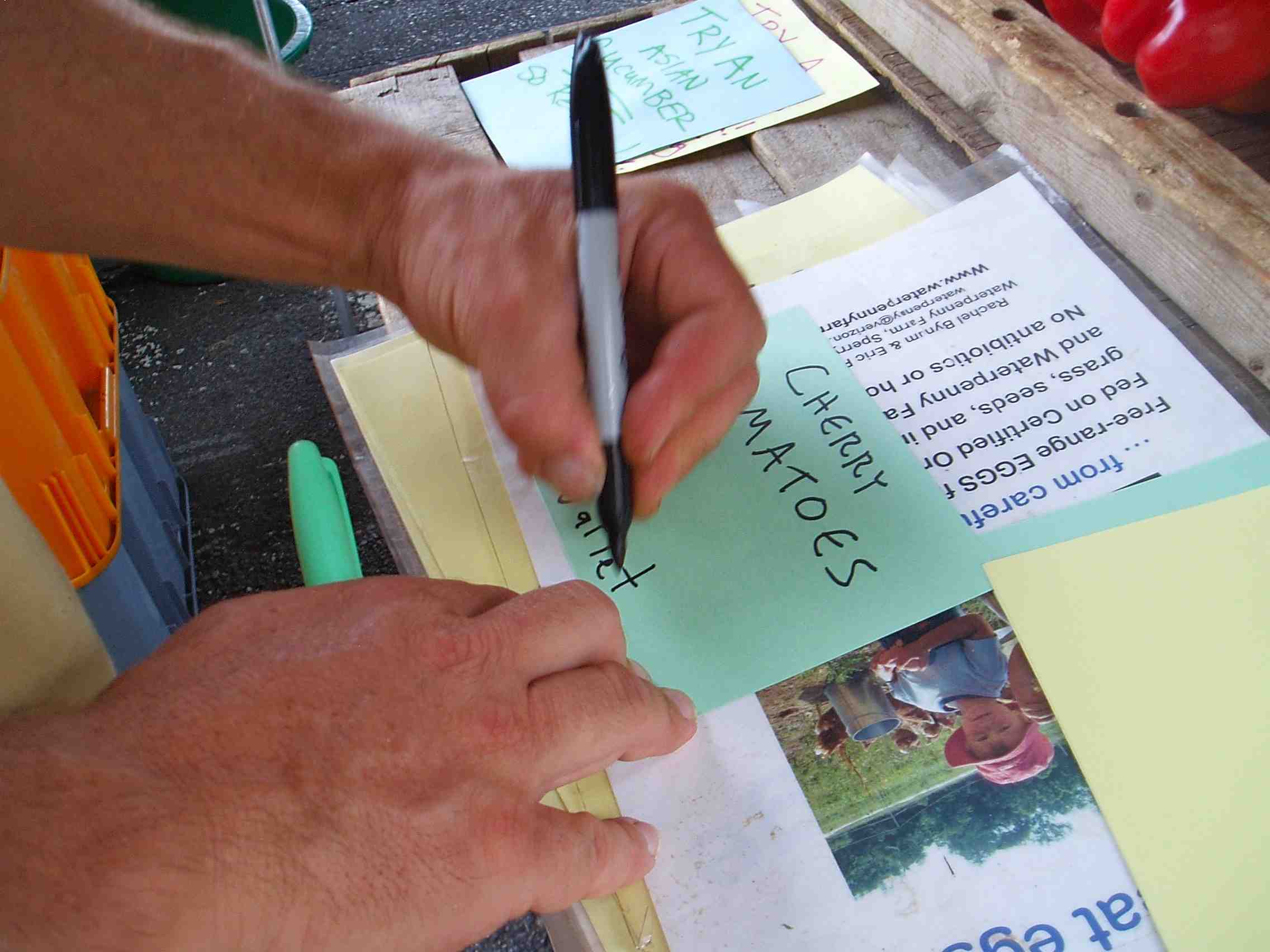

Whether we're writing a sign for cherry tomatoes or our own version of the Great American Novel, one thing is certain: no one expects a farmer to have perfect handwriting! This is my friend Eric Plaksin's hand, a fellow southpaw.

After a summer’s worth of editing on my forthcoming farming book, I’m at peace with the fact that not everything I wanted to include will find its way into the final manuscript. Farming is already hard work, but writing a book about farming somehow makes the challenge seem double. Still, I’ve enjoyed every minute of it, and hopefully it shines through in the work.

I’m sharing a section of Chapter Two that ended up on the cutting room floor. This particular piece had remained in the manuscript until very recently, but as my editor wisely pointed out, the overall energy of the chapter was lacking something… it needed a little more action. So, as much as I loved the following story, I ended up replacing it with a scene where I have to jump for my life off of an out-of-control tractor before it slammed into a tree. You know, no big whoop.

In the original chapter, I’ve just explained how my grandparents successfully farmed for nearly seventy five years. Now, as a twenty-one year old just starting out, I’m struggling with the challenge of living up to their legacy:

A decade earlier, at the age of eleven, I announced one summer morning that I would paint the wooden fence that encompassed my grandparent’s yard. I had seen the farm hands working on it, making repairs, rehanging the gates. I wanted very much to be like them, to prove to my family that I knew what it took to be a real farmer.

The fence was an old fashioned blend of form and function.Constructed of four boards, the tops and bottoms ran parallel to the ground, while the middle boards crossed as an X in the center. The pattern repeated itself at each post, roughly every eight feet. Supplied with a bucket of white paint, a brush, and a scraper for dislodging the infinite number of flaking paint chips, I informed my family that I would have the entire job finished by noon. Accordingly, I started work at about 11:45 a.m.

After an hour, my great aunt Suzanne, in her mid eighties but still nimble enough to shell a five gallon bucket of peas in a spare moment, tottered out to check on my progress. Born in 1901, she had personally known former slaves, and soldiers who had fought in the Civil War. She referred to anyone under the age of forty as ‘child.’

Not more than five feet tall, we already stood eye to eye. She took silent appraisal of the work I had accomplished so far.

“Well,” she said at last, “that’s a nice job you’re doing there.” She glanced at her wristwatch, squinting. “A little slow going, though, don’t you think?”

I tried not to appear crest fallen. “What do you mean? I thought I was doing a good job.”

“Oh, you are, child. You are. But, see, you’ve only done eight feet in an hour’s time.” She gestured down the fence, which extended down the lane, back the other side, then around the sizable yard. All told, there was easily a half a mile left to do. “At this rate,” she chided good naturedly, “you’ll be out here until Thanksgiving.”

It certainly was going a little slower going than I had imagined. Feeling defensive, I searched for the best way to justify my technique.

“I guess,” I said at last, “I guess, aunt Suzanne, I just take a lot of pride in my work.”

I stood my ground as only an eleven year old can stand, paint bespattered from head to toe, my hair tousled from effort. The bucket of paint was still nearly full, and the scraper laid abandoned in the thick grass. My great aunt positively hooted with laughter.

“Oh, I see. I see.”

I tried to figure out what was so funny, clueless as to what prompted her response. “Well, child,” she said warmly, patting me gently on the shoulder. “You be proud of your work. It’s a fine thing to be. But,” she intoned, with benevolent wisdom. “Don’t let that keep you from getting to the end of this fence.”

As best as I can remember, pride must have won out after all. Either that, or an empty stomach. I painted precisely one more section, then abandoned my fence painting dreams in favor of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Looking back on it now, how many men, and how many hours, would it have taken to properly scrape and paint that fence? Extra time would be needed to replace the occasional broken board, or rotten post. Young saplings and wild rosebushes had to be trimmed, and loose nails hammered. Perhaps six grown men, working morning till night? Who really knew?

That was just one fence, and I was just one man. My grandfather had miles of fence, a dozen barns, and crop fields extending into the horizon. I wondered how he had done it, how he had paid all those men, constructed all those fences, successfully managing it all for over half a century. Standing on the front porch of our family’s house, looking down the lane, I was struck by the realization that the fence of my childhood was now gone, worn away by passing time.

I thought back to those fences, the miles of white boards stretching into the horizon, and had an epiphany. I might be carrying on the family tradition, but it wasn’t my duty to rebuild my grandfather’s wooden fences, the ones that needed an army of men just to maintain them. Those fences belonged to a farm of the past.

Instead, I was here to build my own fences, following my own sense of direction. Our farm might retain the very best of the old ways, but the time had come to fit into a modern, changing world. I had to discover a new alternative to those high paying jobs just over the mountain.

At the end of the day, when I imagined setting the final post, hammering the final nail and hanging the gate plumb and nearly perfect, one thought made me especially happy. It was my fence now, and despite the white boards of my childhood, I could paint it any color beneath the sky. The thought of it made me want to get started right away.

That’s it… what do you think? For next week, we’re working on a video about how we load our free-range pigs on pasture.

Please ‘like’ our family farm, and we’ll keep the stories coming! Smith Meadows Facebook

Please ‘like’ our family farm, and we’ll keep the stories coming! Smith Meadows Facebook

Leave a Reply